Printable Manual: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 58: | Line 58: | ||

===The Alexander-Conway Polynomial=== |

===The Alexander-Conway Polynomial=== |

||

{{:The Alexander-Conway Polynomial}} |

{{:The Alexander-Conway Polynomial}} |

||

===The Multivariable Alexander Polynomial=== |

|||

{{:The Multivariable Alexander Polynomial}} |

|||

===The Determinant and the Signature=== |

===The Determinant and the Signature=== |

||

{{:The Determinant and the Signature}} |

{{:The Determinant and the Signature}} |

||

Revision as of 14:20, 5 September 2005

This manual describes the Mathematica package KnotTheory`, the main tool used to produce The Knot Atlas.

Return to the wiki manual.

Acknowledgement

This Atlas is partially (and indirectly) supported by NSERC grant RGPIN 262178. As a Wiki project, it doesn't make sense anymore to acknowledge individual contributors. Yet for historical purposes, here's our acknowledgement as of the conversion to Wiki formnat on August 2005:

- Jana Archibald, for writing the program

Alexander[K, r]. - Sergei Chmutov, for spotting a typo.

- David De Wit, for a bug report.

- Ralph Furmaniak, for help with our link to Knotilus (see Gauss Codes).

- Stavros Garoufalidis, for jointly writing the program ColouredJones (see The Coloured Jones Polynomials).

- Thomas Gittings, for the minimum braid representatives for the knots with up to 10 crossings (see Braid Representatives).

- Jeremy Green, for his java implementation of

Kh(see Khovanov Homology). - Thang Le, for supplying some of the formulas used in the program ColouredJones (see The Coloured Jones Polynomials).

- Rick Litherland, for spotting a sneaky bug in the program

KnotSignature. - Charles Livingston, for allowing us to bundle data from his Table of Knot Invariants.

- Scott Morrison, for a bug report and for writing the programs to compute the HOMFLY-PT and Kauffman polynomials (see The HOMFLY-PT Polynomial and The Kauffman Polynomial).

- Bertrand Patureau-Mirand, for informing us of some mismatches in the link tables (now corrected).

- Jozef Przytycki, for correcting a typo.

- Stuart Rankin, for help with our link to Knotilus (see Gauss Codes).

- Emily Redelmeier, for writing the program DrawPD (see Drawing Planar Diagrams).

- Siddarth Sankaran, for writing the conversion program between Gauss codes and PD codes and for writing MorseLink and DrawMorseLink.

- Alexander Shumakovitch, for his help with signature computations (see The Determinant and the Signature).

- Alexander Stoimenow, for the knot presentations for the knots in the Rolfsen table and some further remarks.

- Z-X. Tao, for noticing problems with the knots 10_83 and 10_86.

- Morwen Thistlethwaite, for the pictures of links and of 11 crossing knots.

- Dylan Thurston, for writing an early routine to translate from Hoste-Thistlethwaite's DT codes to my "PD Presentations".

Setup

Start by downloading the file KnotTheory.zip (around 15MB), and unpack it. This will create a subdirectory KnotTheory/ in your current working directory. This done, no installation is required (though you may wish to check out Further Data Files and/or Setting the Path below). Start Mathematica and you're ready to go:

In[2]:= << KnotTheory`

Loading KnotTheory` version of March 22, 2011, 21:10:4.67737. Read more at http://katlas.org/wiki/KnotTheory.

Notice the little "prime" at the end of KnotTheory above. It is a backquote (find it on the upper left side of most keyboards) and not a quote, and it really has to be there for things to work.

Let us check that everything is working well:

In[3]:=

|

Alexander[Knot[6, 2]][t]

|

Out[3]=

|

-2 3 2

-3 - t + - + 3 t - t

t

|

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

Thus on the day this manual page was last changed, we had:

In[7]:=

|

{KnotTheoryVersion[], KnotTheoryVersionString[]}

|

Out[7]=

|

{{2011, 3, 22, 21, 10, 4.67737}, March 22, 2011, 21:10:4.67737}

|

In[8]:=

|

KnotTheoryWelcomeMessage[]

|

Out[8]=

|

Loading KnotTheory` version of March 22, 2011, 21:10:4.67737.

Read more at http://katlas.org/wiki/KnotTheory.

|

| ||||

In[10]:=

|

KnotTheoryDirectory[]

|

Out[10]=

|

C:\Documents and Settings\pc\Documenti\Wolfram\KnotTheory

|

KnotTheoryDirectory may not work under some operating systems/environments. Please let Dror know if you encounter any difficulties.

Notes

Precomputed Data

KnotTheory` comes with a certain amount of precomputed data which is loaded "on demand" just when it is needed. When a precomputed data file is read by KnotTheory`, a notification message is displayed. To prevent these messages from appearing execute the command Off[KnotTheory::loading].

Further Data Files

To access the Hoste-Thistlethwaite enumeration of knots with 12 to 16 crossings (see Naming and Enumeration), also download either the file DTCodes4Knots12To16.tar.gz or the file DTCodes4Knots12To16.zip (about 9MB each), and unpack either one into the directory KnotTheory/.

Setting the Path

The directions above are written on the assumption that the package KnotTheory` (more precisely, the directory KnotTheory/ containing the files that make this package), is somewhere on your Mathematica search path. Usually this will be the case if KnotTheory/ is a subdirectory of your current working directory. If for some reason Mathematica cannot find KnotTheory`, you may tell it where to look in either of the following three ways. Assume KnotTheory/ is a subdirectory of FullPathToKnotTheory:

- If you are using KnotTheory` rarely and you don't want to change system defaults, evaluate AppendTo[$Path,"FullPathToKnotTheory"] within Mathematica before attempting to load KnotTheory`.

- If you plan to use KnotTheory` often, you may want to move the directory KnotTheory/ into one of the directories on your path. Evaluate $Path within Mathematica to see what those are.

- Alternatively, you may permanently add FullPathToKnotTheory to your $Path. To do that, find your Mathematica base directory by evaluating $UserBaseDirectory (on Dror's laptop, this comes out to be C:\Users\Dror\AppData\Roaming\Mathematica), and then add the line AppendTo[$Path,"FullPathToKnotTheory/"] to the file $BaseDirectory/Kernel/init.m and restart Mathematica.

Naming and Enumeration

KnotTheory` comes loaded with some knot tables; currently, the Rolfsen table of prime knots with up to 10 crossings [Rolfsen], the Hoste-Thistlethwaite tables of prime knots with up to 16 crossings and the Thistlethwaite table of prime links with up to 11 crossings (see Knotscape):

(For In[1] see Setup)

| ||||

| ||||

6_1 |

9_46 |

Thus, for example, let us verify that the knots 6_1 and 9_46 have the same Alexander polynomial:

In[4]:=

|

Alexander[Knot[6, 1]][t]

|

Out[4]=

|

2

5 - - - 2 t

t

|

In[5]:=

|

Alexander[Knot[9, 46]][t]

|

Out[5]=

|

2

5 - - - 2 t

t

|

L6a4 |

We can also check that the Borromean rings, L6a4 in the Thistlethwaite table, is a 3-component link:

In[6]:=

|

Length[Skeleton[Link[6, Alternating, 4]]]

|

Out[6]=

|

3

|

| ||||

| ||||

Thus at the moment there are 1701936 knots and 5700 links known to KnotTheory`:

In[9]:=

|

Length /@ {AllKnots[{0,16}], AllLinks[{2,12}]}

|

Out[9]=

|

{1701936, 5700}

|

In[10]:=

|

Show[DrawPD[Knot[13, NonAlternating, 5016], {Gap -> 0.025}]]

|

| |

Out[10]=

|

-Graphics-

|

(Shumakovitch had noticed that this nice knot has interesting Khovanov homology; see [Shumakovitch]).

T(5,3) |

In addition to the tables, KnotTheory` also knows about torus knots:

| ||||

| ||||

For example, the torus knots T(5,3) and T(3,5) have different presentations with different numbers of crossings, but they are in fact isotopic, and hence they have the same invariants (and in particular the same type 3 Vassiliev invariant ):

In[13]:=

|

Crossings /@ {TorusKnot[5, 3], TorusKnot[3, 5]}

|

Out[13]=

|

{10, 12}

|

In[14]:=

|

Vassiliev[3] /@ {TorusKnot[5, 3], TorusKnot[3, 5]}

|

Out[14]=

|

{20, 20}

|

KnotTheory` knows how to plot torus knots; see Drawing with TubePlot.

You can also use the function Knot to parse certain string representations of named knots:

In[15]:=

|

Knot /@ {"K11a14", "11a_14", "L8a1", "T(3,5)"}

|

Out[15]=

|

{Knot[11, Alternating, 14], If[11 a <= 10 &&

14 <= NumberOfKnots[11 a, Alternating] +

NumberOfKnots[11 a, NonAlternating],

Knot @@ KnotTheory`Naming`s$3008], Link[8, Alternating, 1],

TorusKnot[3, 5]}

|

In the opposite direction, the function NameString produces the standard name for a knot, used throughout the Knot Atlas.

In[16]:=

|

NameString /@ {Knot[11, Alternating, 14], TorusKnot[3,5]}

|

Out[16]=

|

{K11a14, T(3,5)}

|

References

[Rolfsen] ^ D. Rolfsen, Knots and Links, Publish or Perish, Mathematics Lecture Series 7, Wilmington 1976.

[Shumakovitch] ^ A. Shumakovitch, Torsion of the Khovanov Homology, arXiv:math.GT/0405474.

Presentations

KnotTheory` uses several presentations for knots/links.

- Planar Diagrams

- Gauss Codes

- DT (Dowker-Thistlethwaite) Codes

- Braid Representatives

- MorseLink Presentations

- Arc Presentations

- Conway Notation

Planar Diagrams

In the "Planar Diagrams" (PD) presentation we present every knot or link diagram by labeling its edges (with natural numbers, 1,...,n, and with increasing labels as we go around each component) and by a list crossings presented as symbols where , , and are the labels of the edges around that crossing, starting from the incoming lower edge and proceeding counterclockwise. Thus for example, the PD presentation of the knot above is:

(This of course is the Miller Institute knot, the mirror image of the knot 6_2)

(For In[1] see Setup)

|

| ||||||||

| ||||

Thus, for example, let us compute the determinant of the above knot:

In[5]:=

|

K = PD[

X[1,9,2,8], X[3,10,4,11], X[5,3,6,2],

X[7,1,8,12], X[9,4,10,5], X[11,7,12,6]

];

|

In[6]:=

|

Alexander[K][-1]

|

Out[6]=

|

-11

|

Some further details

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

For example, we could add an extra "point" on the Miller Institute knot, splitting edge 12 into two pieces, labeled 12 and 13:

In[10]:=

|

K1 = PD[

X[1,9,2,8], X[3,10,4,11], X[5,3,6,2],

X[7,1,8,13], X[9,4,10,5], X[11,7,12,6],

P[12,13]

];

|

At the moment, many of our routines do not know to ignore such "extra points". But some do:

In[11]:=

|

Jones[K][q] == Jones[K1][q]

|

Out[11]=

|

True

|

| ||||

Hence we can verify that the A2 invariant of the unknot is :

In[13]:=

|

A2Invariant[Loop[1]][q]

|

Out[13]=

|

-2 2

1 + q + q

|

Gauss Codes

The Gauss Code of an -crossing knot or link is obtained as follows:

- Number the crossings of from 1 to in an arbitrary manner.

- Order the components of is some arbitrary manner.

- Start "walking" along the first component of , taking note of the numbers of the crossings you've gone through. If in a given crossing you cross on the "over" strand, write down the number of that crossing. If you cross on the "under" strand, write down the negative of the number of that crossing.

- Do the same for all other components of (if any).

The resulting list of signed integers (in the case of a knot) or list of lists of signed integers (in the case of a link) is called the Gauss Code of . KnotTheory` has some rudimentary support for Gauss codes:

(For In[1] see Setup)

| ||||

Thus for example, the Gauss codes for the trefoil knot and the Borromean link are:

In[3]:=

|

GaussCode /@ {Knot[3, 1], Link[6, Alternating, 4]}

|

Out[3]=

|

{GaussCode[-1, 3, -2, 1, -3, 2],

GaussCode[{1, -6, 5, -3}, {4, -1, 2, -5}, {6, -4, 3, -2}]}

|

3_1 |

L6a4 |

Ralph Furmaniak, working under the guidance of Stuart Rankin and Ortho Flint at the University of Western Ontario, wrote a web-based server called "Knotilus" that takes Gauss codes and outputs pictures of the desired knots and links in several standard image formats.

| ||||

Thus,

In[5]:=

|

KnotilusURL /@ {Knot[3, 1], Link[6, Alternating, 4]}

|

Out[5]=

|

{http://srankin.math.uwo.ca/cgi-bin/retrieve.cgi/-1,3,-2,1,-3,2/goTop.h\

tml, http://srankin.math.uwo.ca/cgi-bin/retrieve.cgi/1,-6,5,-3:4,-1,\

2,-5:6,-4,3,-2/goTop.html}

|

DT (Dowker-Thistlethwaite) Codes

Knots

The "DT Code" ("DT" after Clifford Hugh Dowker and Morwen Thistlethwaite) of a knot is obtained as follows:

- Start "walking" along and count every crossing you pass through. If has crossings and given that every crossing is visited twice, the count ends at . Label each crossing with the values of the counter when it is visited, though when labeling by an even number, take it with a minus sign if you are walking "over" the crossing.

- Every crossing is now labeled with two integers whose absolute values run from to . It is easy to see that each crossing is labeled with one odd integer and one even integer. The DT code of is the list of even integers paired with the odd integers 1, 3, 5, ..., taken in this order. Thus for example the pairing for the knot in the figure below is , and hence its DT code is (and as DT codes are insensitive to overall mirrors, this is equivalent to ).

KnotTheory` has some rudimentary support for DT codes:

(For In[1] see Setup)

| ||||

Thus for example, the DT codes for the last 9 crossing alternating knot 9_41 and the first 9 crossing non alternating knot 9_42 are:

In[3]:=

|

dts = DTCode /@ {Knot[9, 41], Knot[9, 42]}

|

Out[3]=

|

{DTCode[6, 10, 14, 12, 16, 2, 18, 4, 8],

DTCode[4, 8, 10, -14, 2, -16, -18, -6, -12]}

|

(The DT code of an alternating knot is always a sequence of positive numbers but the DT code of a non alternating knot contains both signs.)

9_41 |

9_42 |

DT codes and Gauss codes carry the same information and are easily convertible:

In[4]:=

|

gcs = GaussCode /@ dts

|

Out[4]=

|

{GaussCode[1, -6, 2, -8, 3, -1, 4, -9, 5, -2, 6, -4, 7, -3, 8, -5, 9,

-7], GaussCode[1, -5, 2, -1, 3, 8, -4, -2, 5, -3, -6, 9, -7, 4, -8,

6, -9, 7]}

|

In[5]:=

|

DTCode /@ gcs

|

Out[5]=

|

{DTCode[6, 10, 14, 12, 16, 2, 18, 4, 8],

DTCode[4, 8, 10, -14, 2, -16, -18, -6, -12]}

|

Conversion between DT codes and/or Gauss codes and PD codes is more complicated; the harder side, going from DT/Gauss to PD, was written by Siddarth Sankaran at the University of Toronto:

In[6]:=

|

PD[DTCode[4, 6, 2]]

|

Out[6]=

|

PD[X[4, 2, 5, 1], X[6, 4, 1, 3], X[2, 6, 3, 5]]

|

Links

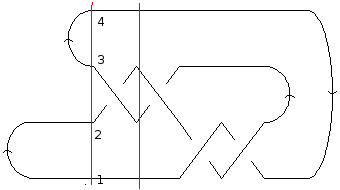

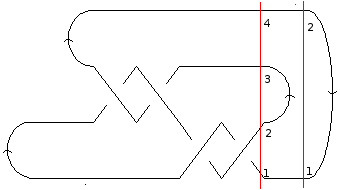

DT Codes for links are defined in a similar way (see [DollHoste]). Follow the same numbering process as for knots, except when you finish traversing one component, jump straight to the next. It is not difficult to see that there is always a choice of starting points along the components for which the resulting pairing is a pairing between odd and even numbers. (On the figure above one possible choice is indicated). Again, it is enough to only list the even numbers corresponding to ; call the resulting list . (Above, ). Notice that the odd indices are naturally subdivided into sublists according to the component of the link on which they lie, and this induces a subdivision of into sublists. Thus with the choices made in the figure above, the DT code for the link L7n2 is .

KnotTheory` knows about DT codes for links:

In[7]:=

|

DTCode[Link[7, NonAlternating, 2]]

|

Out[7]=

|

DTCode[{6, -8}, {-10, 12, -14, 2, -4}]

|

In[8]:=

|

MultivariableAlexander[DTCode[{6, -8}, {-10, 12, -14, 2, -4}]][t]

|

Out[8]=

|

(-1 + t[1]) (-1 + t[2])

-----------------------

Sqrt[t[1]] Sqrt[t[2]]

|

[DollHoste] ^ H. Doll and J. Hoste, A tabulation of oriented links, Mathematics of Computation 57-196 (1991) 747-761.

Braid Representatives

Every knot and every link is the closure of a braid. KnotTheory` can also represent knots and links as braid closures:

(For In[1] see Setup)

|

| ||||||||

| ||||

Thus for example,

In[5]:=

|

br1 = BR[2, {-1, -1, -1}];

|

In[6]:=

|

PD[br1]

|

Out[6]=

|

PD[X[6, 3, 1, 4], X[4, 1, 5, 2], X[2, 5, 3, 6]]

|

In[7]:=

|

Jones[br1][q]

|

Out[7]=

|

-4 -3 1

-q + q + -

q

|

In[8]:=

|

Mirror[br1]

|

Out[8]=

|

BR[2, {1, 1, 1}]

|

T(5,4) |

K11a362 |

KnotTheory` has the braid representatives of some knots and links pre-loaded, and for all other knots and links it will find a braid representative using Vogel's algorithm. Thus for example,

In[9]:=

|

BR[TorusKnot[5, 4]]

|

Out[9]=

|

BR[4, {1, 2, 3, 1, 2, 3, 1, 2, 3, 1, 2, 3, 1, 2, 3}]

|

In[10]:=

|

BR[Knot[11, Alternating, 362]]

|

Out[10]=

|

BR[10, {1, 2, -3, -4, 5, 6, 5, 4, 3, -2, -1, -4, 3, -2, -4, 3, 5, 4,

-6, 7, -6, 5, 8, 7, 6, 5, -4, -3, 2, 5, -6, 9, -8, 7, -6, 5, 4, -3,

5, 6, 5, 4, 5, -7, 8, -7, 6, 5, -9, -8, -7}]

|

(As we see, Vogel's algorithm sometimes produces scary results. A 51-crossings braid representative for an 11-crossing knot, in the case of K11a362).

10_1 |

5_2 |

The minimum braid representative of a given knot is a braid representative for that knot which has a minimal number of braid crossings and within those braid representatives with a minimal number of braid crossings, it has a minimal number of strands (full details are in [Gittings]). Thomas Gittings kindly provided us the minimum braid representatives for all knots with up to 10 crossings. Thus for example, the minimum braid representative for the knot 10_1 has length (number of crossings) 13 and width 6 (number of strands, also see Invariants from Braid Theory):

In[11]:=

|

br2 = BR[Knot[10, 1]]

|

Out[11]=

|

BR[6, {-1, -1, -2, 1, -2, -3, 2, -3, -4, 3, 5, -4, 5}]

|

In[12]:=

|

Show[BraidPlot[CollapseBraid[br2]]]

|

| |

Out[12]=

|

-Graphics-

|

Already for the knot 5_2 the minimum braid is shorter than the braid produced by Vogel's algorithm. Indeed, the minimum braid is

In[13]:=

|

Show[BraidPlot[CollapseBraid[BR[Knot[5, 2]]]]]

|

| |

Out[13]=

|

-Graphics-

|

To force KnotTheory` to run Vogel's algorithm on 5_2, we first convert it to its PD form,

In[14]:=

|

pd = PD[Knot[5, 2]]

|

Out[14]=

|

PD[X[1, 4, 2, 5], X[3, 8, 4, 9], X[5, 10, 6, 1], X[9, 6, 10, 7],

X[7, 2, 8, 3]]

|

and only then run BR:

In[15]:=

|

Show[BraidPlot[CollapseBraid[BR[pd]]]]

|

| |

Out[15]=

|

-Graphics-

|

(Check Drawing Braids for information about the command BraidPlot and the related command CollapseBraid.)

[Gittings] ^ T. A. Gittings, Minimum braids: a complete invariant of knots and links, arXiv:math.GT/0401051.

MorseLink Presentations

The MorseLink presentation describes an oriented knot or link diagram as a sequence of 'events'. To begin, we fix an axis in the plane, so that each event in the MorseLink description occurs in successive intervals along this axis. The 'events' that comprise a knot or link are 'cups' (creations), 'caps' (annihilations), and crossings, where cups and caps are the minima and maxima (respectively) relative to the chosen axis. The conventions used by MorseLink are as follows:

- Cup[m,n] represents a creation, where the new strands are in position m and n, with m and n differing by 1, and is directed from m to n.

- Cap[m,n] represents an annihilation of the strands m and n, again with m and n differing by 1, and is directed from m to n.

- X[n, d, a, b] is a crossing of the n-th and the (n+1)-th strands. 'd' signifies whether the n-th strand goes 'Over' or 'Under' the (n+1)-th strand. 'a' indicates whether the n-th strand is moving 'Up' or 'Down' through the crossing, relative to the chosen axis; 'b' does the same for the (n+1)-th strand.

For concreteness, let us find a MorseLink presentation of the knot 4_1, based on the following diagram:

We fix the chosen axis to be the positive axis, and we number the strands at each interval from bottom to top. Clearly the first event to take place is a cup, creating strands 1 and 2, and directed from 1 to 2. The next event is also a cup; this time, the strands 3 and 4 are created, from 3 to 4. So the first two elements of our MorseLink presentation are {Cup[1,2], Cup[3,4], ...}.

The next event to take place is a crossing. This crossing has strand 2 going under strand 3; following the orientations, strand 2 moves to the right through the crossing, while strand 3 comes from the left. Since the chosen axis is pointing to the right, this event is described as X[2, Under, Up, Down]. We may proceed in a similar way for the rest of the crossings.

After three more crossings, we encounter two cap events. The first annihilates strands 2 and 3, and is directed from 2 to 3. The second annihilates strands 1 and 2, but is directed from 2 to 1. So the MorseLink presentation for the knot 4_1 is given by: MorseLink[Cup[1,2], Cup[3,4], X[2 , Under, Up, Down], X[2, Under, Down, Up], X[1, Over, Down, Up], X[1, Over, Up, Down], Cap[2,3], Cap[2,1]].

Further notes

KnotTheory` knows about Morse link presentations: (For In[1] see Setup)

|

| ||||||||

- Obviously, there is no unique Morse link presentation for a knot. One presentation may be considered 'better' than another if it generally has fewer strands. Unfortunately, this program makes only a half-hearted attempt in coming up with such presentations; it does a creation only when it can no longer do any caps or crossings, but exhibits a lack of foresight into which edges to create.

Graphical Output

KnotTheory` can draw knots and links in several ways.

Drawing Planar Diagrams

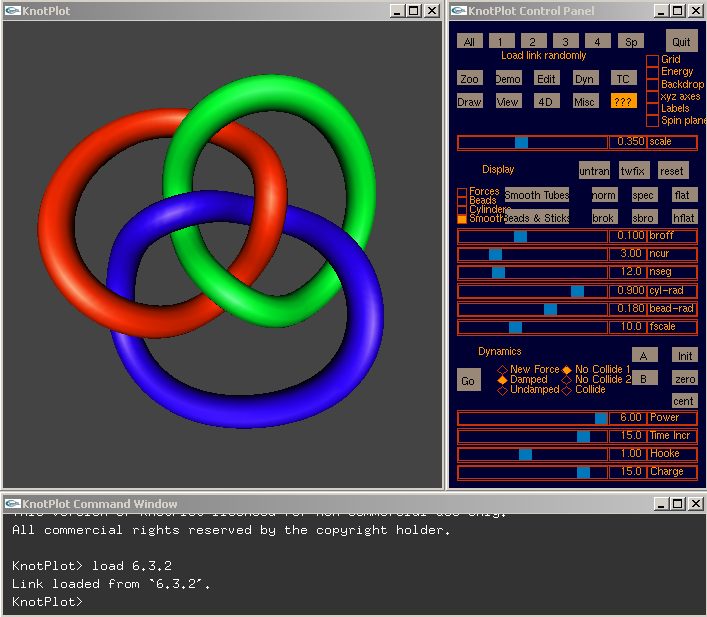

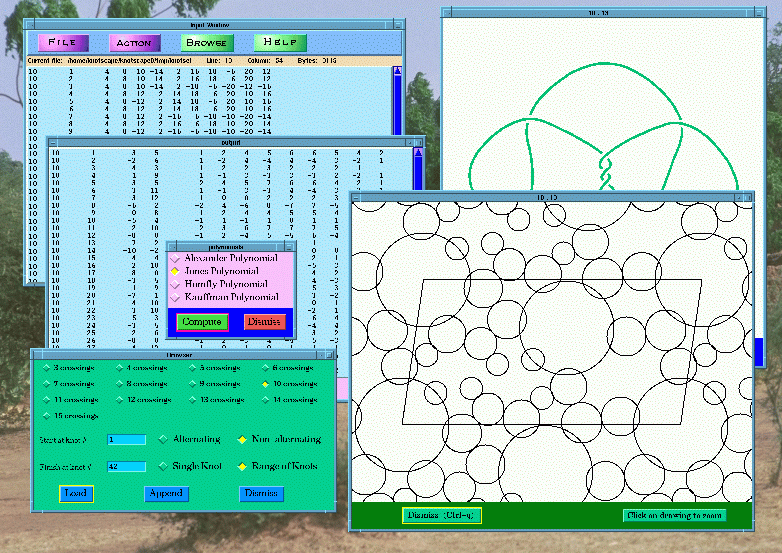

My summer student Emily Redelmeier is in the process of writing a program that uses circle packing to draw an arbitrary object given as a PD as in Planar Diagrams. At the moment her program is still slow, limited and sometimes buggy, but it is already quite useful, as the following lines show:

(For In[1] see Setup)

|

| ||||||||

Thus, for example, here's the torus knot T(4,3):

In[4]:=

|

Show[DrawPD[TorusKnot[4, 3]]]

|

| |

Out[4]=

|

-Graphics-

|

One problem we currently have is that crossings come out at non-uniform sizes, hence in the picture below you may need magnifying glasses to decide who's over and who's under:

In[5]:=

|

MillettUnknot = PD[

X[1,10,2,11], X[9,2,10,3], X[3,7,4,6], X[15,5,16,4],

X[5,17,6,16],X[7,14,8,15], X[8,18,9,17], X[11,18,12,19],

X[19,12,20,13], X[13,20,14,1]

];

|

In[6]:=

|

Show[DrawPD[MillettUnknot]]

|

| |

Out[6]=

|

-Graphics-

|

In such a situation, the option Gap is sometimes handy:

In[7]:=

|

Show[DrawPD[MillettUnknot, {Gap -> 0.03}]]

|

| |

Out[7]=

|

-Graphics-

|

How does it work?

DrawPD uses Andreev's theorem [Andreev1], [Andreev2], which states that every planar graph can be realized, nearly uniquely, as the graph of tangencies of circles drawn within the unit disk. That is, to every vertex of one may associate a disk within the unit disk, so that the interiors of these disks are disjoint and they are tangent iff the corresponding vertices are connected by an edge. The Andreev "circle packing" corresponding to the knot 4_1 is the first picture on the right (circle 13 is the unit disk itself).

But now every ingredient of the original knot (every arc, crossing and face) has a disk in the plane in which it can be cleanly drawn and clashes are guaranteed not to occur. Furthermore, knowing the precise coordinates of all the tangency points allows us to represent each ingredient by some nice smooth arcs that meet smoothly. The result is the second picture on the right. Removing all the circles, what remains is the desired clean planar picture of 4_1.

[Andreev1] ^ A. Andreev, On convex polyhedra in Lobacevskii spaces (in Russian), Math. Sbornik USSR, Nov. Ser. 81 (1970) 445-478.

[Andreev2] ^ A. Andreev, On convex polyhedra of finite volume in Lobacevskii spaces (in Russian), Math. Sbornik USSR, Nov. Ser. 83 (1970) 256-260.

Drawing MorseLink Presentations

KnotTheory` can also draw knots and links via their Morse link presentations:

(For In[1] see Setup)

|

| ||||||||

For example, here is the 11-crossing alternating link L11a548:

In[4]:=

|

Show[DrawMorseLink[Link[11, Alternating, 548]]]

|

| |

Out[4]=

|

-Graphics-

|

There are two options available for this program. Adding the option Gap -> g, where g is between 0 and 1, changes the amount of white space in each crossing; increasing g increases the white space, making large diagrams more visible. The option ArrowSize -> as (where as is between 0 and 1) alters the size of the orientation arrows. Here is the same drawing as above, but this time the orientation arrows are gone and the crossings are more clear:

In[6]:=

|

Show[DrawMorseLink[

Link[11, Alternating, 548],

ArrowSize -> 0, Gap -> 0.65

]]

|

| |

Out[6]=

|

-Graphics-

|

Drawing Braids

(For In[1] see Setup)

| ||||

Thus for example,

In[3]:=

|

br = BR[5, {{1,3}, {-2,-4}, {1, 3}}];

|

In[4]:=

|

Show[BraidPlot[br]]

|

| |

Out[4]=

|

-Graphics-

|

BraidPlot takes several options:

In[5]:=

|

Options[BraidPlot]

|

Out[5]=

|

{Mode -> Graphics, Images -> {0.gif, 1.gif, 2.gif, 3.gif, 4.gif},

HTMLOpts -> , WikiOpts -> }

|

The Mode option to BraidPlot defaults to "Graphics", which produces output as above. An alternative is setting Mode -> "HTML", which produces an HTML <table> that can be readily inserted into HTML documents:

In[6]:=

|

BraidPlot[br, Mode -> "HTML"]

|

Out[6]=

|

<table cellspacing=0 cellpadding=0 border=0>

<tr><td><img src=1.gif><img src=0.gif><img src=1.gif></td></tr>

<tr><td><img src=2.gif><img src=3.gif><img src=2.gif></td></tr>

<tr><td><img src=1.gif><img src=4.gif><img src=1.gif></td></tr>

<tr><td><img src=2.gif><img src=3.gif><img src=2.gif></td></tr>

<tr><td><img src=0.gif><img src=4.gif><img src=0.gif></td></tr>

</table>

|

The table produced contains an array of image inclusions that together draws the braid using 5 fundamental building blocks: a horizontal "unbraided" line (0.gif above), the upper and lower halves of an overcrossing (1.gif and 2.gif above) and the upper and lower halves of an underfcrossing (3.gif and 4.gif above).

Assuming 0.gif through 4.gif are ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() , the above table is rendered as follows:

, the above table is rendered as follows:

The meaning of the Images option to BraidPlot should be clear from reading its default definition:

In[7]:=

|

Images /. Options[BraidPlot]

|

Out[7]=

|

{0.gif, 1.gif, 2.gif, 3.gif, 4.gif}

|

The HTMLOpts option to BraidPlot allows to insert options within the HTML <img> tags. Thus

In[8]:=

|

BraidPlot[BR[2, {1, 1}], Mode -> "HTML", HTMLOpts -> "border=1"]

|

Out[8]=

|

<table cellspacing=0 cellpadding=0 border=0>

<tr><td><img border=1 src=1.gif><img border=1 src=1.gif></td></tr>

<tr><td><img border=1 src=2.gif><img border=1 src=2.gif></td></tr>

</table>

|

The above table is rendered as follows:

| ||||

Thus compare the plots of br1 and br2 below:

In[10]:=

|

br1 = BR[TorusKnot[5, 4]]

|

Out[10]=

|

BR[4, {1, 2, 3, 1, 2, 3, 1, 2, 3, 1, 2, 3, 1, 2, 3}]

|

In[11]:=

|

Show[BraidPlot[br1]]

|

| |

Out[11]=

|

-Graphics-

|

In[12]:=

|

br2 = CollapseBraid[BR[TorusKnot[5, 4]]]

|

Out[12]=

|

BR[4, {{1}, {2}, {3, 1}, {2}, {3, 1}, {2}, {3, 1}, {2}, {3, 1}, {2},

{3}}]

|

In[13]:=

|

Show[BraidPlot[br2]]

|

| |

Out[13]=

|

-Graphics-

|

Structure and Operations

(For In[1] see Setup)

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

Thus here's one tautology and one easy example:

In[5]:=

|

Crossings /@ {Knot[0, 1], TorusKnot[11,10]}

|

Out[5]=

|

{0, 99}

|

And another easy example:

In[6]:=

|

K=Knot[6, 2]; {PositiveCrossings[K], NegativeCrossings[K]}

|

Out[6]=

|

{2, 4}

|

| ||||

| ||||

For example,

In[9]:=

|

PositiveQ /@ {X[1,3,2,4], X[1,4,2,3], Xp[1,3,2,4], Xp[1,4,2,3]}

|

Out[9]=

|

{False, True, True, True}

|

| ||||

The connected sum of the knot 4_1 with itself has 8 crossings (unsurprisingly):

In[11]:=

|

K = ConnectedSum[Knot[4,1], Knot[4,1]]

|

Out[11]=

|

ConnectedSum[Knot[4, 1], Knot[4, 1]]

|

In[12]:=

|

Crossings[K]

|

Out[12]=

|

8

|

It is also nice to know that, as expected, the Jones polynomial of is the square of the Jones polynomial of 4_1:

In[13]:=

|

Jones[K][q] == Expand[Jones[Knot[4,1]][q]^2]

|

Out[13]=

|

True

|

4_1 |

8_9 |

It is less nice to know that the Jones polynomial cannot tell apart from the knot 8_9:

In[14]:=

|

Jones[K][q] == Jones[Knot[8,9]][q]

|

Out[14]=

|

True

|

But isn't equivalent to 8_9; indeed, their Alexander polynomials are different:

In[15]:=

|

{Alexander[K][t], Alexander[Knot[8,9]][t]}

|

Out[15]=

|

-2 6 2 -3 3 5 2 3

{11 + t - - - 6 t + t , 7 - t + -- - - - 5 t + 3 t - t }

t 2 t

t

|

Invariants

- Invariants from Braid Theory

- Three Dimensional Invariants

- The Alexander-Conway Polynomial

- The Multivariable Alexander Polynomial

- The Determinant and the Signature

- The Jones Polynomial

- The Coloured Jones Polynomials

- The A2 Invariant

- Quantum knot invariants

- The HOMFLY-PT Polynomial

- The Kauffman Polynomial

- Finite Type (Vassiliev) Invariants

- Khovanov Homology

- Heegaard Floer Knot Homology

- R-Matrix Invariants

Invariants from Braid Theory

The braid length of a knot or a link is the smallest number of crossings in a braid whose closure is . KnotTheory` has some braid lengths preloaded:

(For In[1] see Setup)

| ||||

Note that the braid length of is simply the length of the minimum braid representing (see Braid Representatives):

In[3]:=

|

K = Knot[9, 49]; {BraidLength[K], Crossings[BR[K]]}

|

Out[3]=

|

{11, 11}

|

9_49 |

10_136 |

The braid index of a knot or a link is the smallest number of strands in a braid whose closure is . KnotTheory` has some braid indices preloaded:

|

| ||||||||

Of the 250 knots with up to 10 crossings, only 10_136 has braid index smaller than the width of its minimum braid:

In[6]:=

|

K = Knot[10, 136]; {BraidIndex[K], First@BR[K]}

|

Out[6]=

|

{4, 5}

|

In[7]:=

|

Show[BraidPlot[BR[K]]]

|

| |

Out[7]=

|

-Graphics-

|

Three Dimensional Invariants

(For In[1] see Setup)

Symmetry Type

|

| ||||||||

The inverse of a knot is the knot obtained from it by reversing its parametrization. The mirror of A knot is obtained from by reversing the orientation of the ambient space, or, alternatively, by flipping all the crossings of .

A knot is called "fully amphicheiral" if it is equal to its inverse and also to its mirror. The first knot with this property is

In[4]:=

|

Select[AllKnots[],

(SymmetryType[#] == FullyAmphicheiral) &, 1]

|

Out[4]=

|

{Knot[4, 1]}

|

A knot is called "reversible" if it is equal to its inverse yet it different from its mirror (and hence also from the inverse of its mirror). Many knots have this property; indeed, the first one is:

In[5]:=

|

Select[AllKnots[],

(SymmetryType[#] == Reversible) &, 1]

|

Out[5]=

|

{Knot[3, 1]}

|

A knot is called "positive amphicheiral" if it is different from its inverse but equal to its mirror. There are no such knots with up to 11 crossings.

A knot is called "negative amphicheiral" if it is different from its inverse and its mirror, yet it is equal to the inverse of its mirror. The first knot with this property is

In[6]:=

|

Select[AllKnots[],

(SymmetryType[#] == NegativeAmphicheiral) &, 1]

|

Out[6]=

|

{Knot[8, 17]}

|

Finally, if a knot is different from its inverse, its mirror and from the inverse of its mirror, it is "chiral". The first such knot is

In[7]:=

|

Select[AllKnots[],

(SymmetryType[#] == Chiral) &, 1]

|

Out[7]=

|

{Knot[9, 32]}

|

It is a amusing to take "symmetry type" statistics on all the prime knots with up to 11 crossings:

In[8]:=

|

Plus @@ (SymmetryType /@ Rest[AllKnots[]])

|

Out[8]=

|

216 Chiral + 13 FullyAmphicheiral + 7 NegativeAmphicheiral +

565 Reversible

|

4_1 |

3_1 |

8_17 |

9_32 |

Unknotting Number

The unknotting number of a knot is the minimal number of crossing changes needed in order to unknot .

|

| ||||||||

Of the 512 knots whose unknotting number is known to KnotTheory`, 197 have unknotting number 1, 247 have unknotting number 2, 54 have unknotting number 3, 12 have unknotting number 4 and 1 has unknotting number 5:

In[11]:=

|

Plus @@ u /@ Cases[UnknottingNumber /@ AllKnots[], _Integer]

|

Out[11]=

|

u[0] + 197 u[1] + 247 u[2] + 54 u[3] + 12 u[4] + u[5]

|

There are 4 knots with up to 9 crossings whose unknotting number is unknown:

In[12]:=

|

Select[AllKnots[],

Crossings[#] <= 9 && Head[UnknottingNumber[#]] === List &

]

|

Out[12]=

|

{Knot[9, 10], Knot[9, 13], Knot[9, 35], Knot[9, 38]}

|

9_10 |

9_13 |

9_35 |

9_38 |

3-Genus

A Seifert surface for a knot is a compact oriented surface with boundary . Seifert surfaces exist, but are not unique. The SeifertView programme is a visual implementation of the algorithm of Seifert (1934) for the construction of a Seifert surface from a knot projection. The 3-genus of a knot is the minimal genus of a Seifert surface for that knot.

|

| ||||||||

The highest 3-genus of the knots known to KnotTheory` is , and there is only one knot with up to 11 crossings whose 3-genus is 5:

In[15]:=

|

Max[ThreeGenus /@ AllKnots[]]

|

Out[15]=

|

5

|

In[16]:=

|

Select[AllKnots[], ThreeGenus[#] == 5 &]

|

Out[16]=

|

{Knot[11, Alternating, 367]}

|

K11a367 |

T(11,2) |

(K11a367 is, of couse, also known as the torus knot T(11,2)).

The Conway knot K11n34 is the closure of the braid BR[4, {1, 1, 2, -3, 2, 1, -3, -2, -2, -3, -3}]. Let us compute its 3-genus and compare it with the 3-genus of its mutant companion, the Kinoshita-Terasaka knot K11n42:

In[17]:=

|

ThreeGenus[BR[4, {1, 1, 2, -3, 2, 1, -3, -2, -2, -3, -3}]]

|

Out[17]=

|

3

|

In[18]:=

|

ThreeGenus[Knot[11, NonAlternating, 42]]

|

Out[18]=

|

2

|

K11n34 |

K11n42 |

Bridge Index

The bridge index' of a knot is the minimal number of local maxima (or local minima) in a generic smooth embedding of in .

|

| ||||||||

An often studied class of knots is the class of 2-bridge knots, knots whose bridge index is 2. Of the 49 prime 9-crossings knots, 24 are 2-bridge:

In[21]:=

|

Select[AllKnots[], Crossings[#] == 9 && BridgeIndex[#] == 2 &]

|

Out[21]=

|

{Knot[9, 1], Knot[9, 2], Knot[9, 3], Knot[9, 4], Knot[9, 5],

Knot[9, 6], Knot[9, 7], Knot[9, 8], Knot[9, 9], Knot[9, 10],

Knot[9, 11], Knot[9, 12], Knot[9, 13], Knot[9, 14], Knot[9, 15],

Knot[9, 17], Knot[9, 18], Knot[9, 19], Knot[9, 20], Knot[9, 21],

Knot[9, 23], Knot[9, 26], Knot[9, 27], Knot[9, 31]}

|

Super Bridge Index

The super bridge index of a knot is the minimal number, in a generic smooth embedding of in , of the maximal number of local maxima (or local minima) in a rigid rotation of that projection.

|

| ||||||||

Nakanishi Index

|

| ||||||||

Synthesis

In[26]:=

|

Profile[K_] := Profile[

SymmetryType[K], UnknottingNumber[K], ThreeGenus[K],

BridgeIndex[K], SuperBridgeIndex[K], NakanishiIndex[K]

]

|

In[27]:=

|

Profile[Knot[9,24]]

|

Out[27]=

|

Profile[Reversible, 1, 3, 3, {4, 6}, 1]

|

In[28]:=

|

Ks = Select[AllKnots[], (Crossings[#] == 9 && Profile[#]==Profile[Knot[9,24]])&]

|

Out[28]=

|

{Knot[9, 24], Knot[9, 28], Knot[9, 30], Knot[9, 34]}

|

9_24 |

9_28 |

9_30 |

9_34 |

In[29]:=

|

Alexander[#][t]& /@ Ks

|

Out[29]=

|

-3 5 10 2 3

{13 - t + -- - -- - 10 t + 5 t - t ,

2 t

t

-3 5 12 2 3

-15 + t - -- + -- + 12 t - 5 t + t ,

2 t

t

-3 5 12 2 3

17 - t + -- - -- - 12 t + 5 t - t ,

2 t

t

-3 6 16 2 3

23 - t + -- - -- - 16 t + 6 t - t }

2 t

t

|

The Alexander-Conway Polynomial

(For In[1] see Setup)

|

| ||||||||

| ||||

8_18 |

The Alexander polynomial and the Conway polynomial of a knot always satisfy . Let us verify this relation for the knot 8_18:

In[5]:=

|

alex = Alexander[Knot[8, 18]][t]

|

Out[5]=

|

-3 5 10 2 3

13 - t + -- - -- - 10 t + 5 t - t

2 t

t

|

In[6]:=

|

Expand[Conway[Knot[8, 18]][Sqrt[t] - 1/Sqrt[t]]]

|

Out[6]=

|

-3 5 10 2 3

13 - t + -- - -- - 10 t + 5 t - t

2 t

t

|

The determinant of a knot is . Hence for 8_18 it is

In[7]:=

|

Abs[alex /. t -> -1]

|

Out[7]=

|

45

|

Alternatively (see The Determinant and the Signature):

In[8]:=

|

KnotDet[Knot[8, 18]]

|

Out[8]=

|

45

|

, the (standardly normalized) type 2 Vassiliev invariant of a knot is the coefficient of in its Conway polynomial:

In[9]:=

|

Coefficient[Conway[Knot[8, 18]][z], z^2]

|

Out[9]=

|

1

|

Alternatively (see Finite Type (Vassiliev) Invariants),

In[10]:=

|

Vassiliev[2][Knot[8, 18]]

|

Out[10]=

|

1

|

K11a99 |

K11a277 |

Sometimes two knots have the same Alexander polynomial but different Alexander ideals. An example is the pair K11a99 and K11a277. They have the same Alexander polynomial, but the second Alexander ideal of the first knot is the whole ring while the second Alexander ideal of the second knot is the smaller ideal generated by and by :

In[11]:=

|

{K1, K2} = {Knot[11, Alternating, 99], Knot[11, Alternating, 277]};

|

In[12]:=

|

Alexander[K1] == Alexander[K2]

|

Out[12]=

|

True

|

In[13]:=

|

Alexander[K1, 2][t]

|

Out[13]=

|

{1}

|

In[14]:=

|

Alexander[K2, 2][t]

|

Out[14]=

|

{3, 1 + t}

|

Finally, the Alexander polynomial attains 551 values on the 802 knots known to KnotTheory`:

In[15]:=

|

Length /@ {Union[Alexander[#]& /@ AllKnots[]], AllKnots[]}

|

Out[15]=

|

{551, 802}

|

The Multivariable Alexander Polynomial

(For In[1] see Setup)

|

| ||||||||

L8a21 |

The link L8a21 is symmetric under cyclic permutations of its components but not under interchanging two adjacent components. It is amusing to see how this is reflected in its multivariable Alexander polynomial:

In[3]:=

|

mva = MultivariableAlexander[Link[8, Alternating, 21]][t] /. {

t[1] -> t1, t[2] -> t2, t[3] -> t4, t[4] -> t3

}

|

Out[3]=

|

(-t1 - t2 + t1 t2 - t3 + 2 t1 t3 + t2 t3 - t1 t2 t3 - t4 + t1 t4 +

2 t2 t4 - t1 t2 t4 + t3 t4 - t1 t3 t4 - t2 t3 t4) /

(Sqrt[t1] Sqrt[t2] Sqrt[t3] Sqrt[t4])

|

In[4]:=

|

mva - (mva /. {t1->t2, t2->t3, t3->t4, t4->t1})

|

Out[4]=

|

0

|

In[5]:=

|

Simplify[mva - (mva /. {t1->t2, t2->t1})]

|

Out[5]=

|

(t1 - t2) (t3 - t4)

-----------------------------------

Sqrt[t1] Sqrt[t2] Sqrt[t3] Sqrt[t4]

|

But notice the funny labelling of the components! The program MultivariableAlexander orders the variables in its output (typically denoted t[i]) in the same order as the order of the components of a link L as they appear within Skeleton[L]. Hence we had to rename t[3] to be t4 and t[4] to be t3.

Links with Vanishing Multivariable Alexander Polynomial

There are 11 links with up to 11 crossings whose multivariable Alexander polynomial is . Here they are:

In[6]:=

|

Select[AllLinks[], (MultivariableAlexander[#][t] == 0) &]

|

Out[6]=

|

{Link[9, NonAlternating, 27], Link[10, NonAlternating, 32],

Link[10, NonAlternating, 36], Link[10, NonAlternating, 107],

Link[11, NonAlternating, 244], Link[11, NonAlternating, 247],

Link[11, NonAlternating, 334], Link[11, NonAlternating, 381],

Link[11, NonAlternating, 396], Link[11, NonAlternating, 404],

Link[11, NonAlternating, 406]}

|

L9n27 |

L10n32 |

L10n36 |

L10n107 |

L11n244 |

L11n247 |

L11n334 |

L11n381 |

L11n396 |

L11n404 |

L11n406 |

Dror doesn't understand the multivariable Alexander polynomial well enough to give simple topological reasons for the vanishing of the said polynomial for these knots. (Though see the Talk Page).

Detecting a Link Using the Multivariable Alexander Polynomial

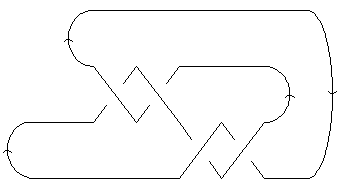

On May 1, 2007 AnonMoos asked Dror if he could identify the link in the figure on the right. So Dror typed:

In[7]:=

|

mva = MultivariableAlexander[L = PD[

X[1, 16, 2, 17], X[3, 15, 4, 14], X[5, 8, 6, 9],

X[7, 21, 8, 20], X[9, 22, 10, 13], X[11, 2, 12, 3],

X[13, 18, 14, 19], X[15, 12, 16, 1], X[17, 11, 18, 10],

X[19, 4, 20, 5], X[21, 7, 22, 6]

]][t]

|

Out[7]=

|

2

-(((-1 + t[1]) (-1 + t[2]) (1 - 2 t[1] + t[1] - 2 t[2] + 2 t[1] t[2] -

2 2 2 2 2

2 t[1] t[2] + t[2] - 2 t[1] t[2] + t[1] t[2] )) /

3/2 3/2

(t[1] t[2] ))

|

We don't know whether our mystery link appears in the link table as is, or as a mirror, or with its two components switched. Hence we let AllPossibilities contain the multivariable Alexander polynomials of all those possibilities:

In[8]:=

|

AllPossibilities = Union[Flatten[

{mva, -mva} /. {{}, {t[1] -> t[2], t[2] -> t[1]}}

]]

|

Out[8]=

|

2

{-(((-1 + t[1]) (-1 + t[2]) (1 - 2 t[1] + t[1] - 2 t[2] +

2 2 2 2 2

2 t[1] t[2] - 2 t[1] t[2] + t[2] - 2 t[1] t[2] + t[1] t[2]

3/2 3/2

)) / (t[1] t[2] )),

2

((-1 + t[1]) (-1 + t[2]) (1 - 2 t[1] + t[1] - 2 t[2] + 2 t[1] t[2] -

2 2 2 2 2

2 t[1] t[2] + t[2] - 2 t[1] t[2] + t[1] t[2] )) /

3/2 3/2

(t[1] t[2] )}

|

Finally, let us locate our link in the link table:

In[9]:=

|

Select[

AllLinks[],

MemberQ[AllPossibilities, MultivariableAlexander[#][t]] &

]

|

Out[9]=

|

{Link[11, Alternating, 289]}

|

And just to be sure,

In[10]:=

|

{Jones[L][q], Jones[Link[11, Alternating, 289]][q]}

|

Out[10]=

|

-(17/2) 4 8 12 16 18 17 15

{q - ----- + ----- - ----- + ---- - ---- + ---- - ---- +

15/2 13/2 11/2 9/2 7/2 5/2 3/2

q q q q q q q

10 3/2 5/2

------- - 7 Sqrt[q] + 3 q - q ,

Sqrt[q]

-(5/2) 3 7 3/2 5/2

-q + ---- - ------- + 10 Sqrt[q] - 15 q + 17 q -

3/2 Sqrt[q]

q

7/2 9/2 11/2 13/2 15/2 17/2

18 q + 16 q - 12 q + 8 q - 4 q + q }

|

Thus the mystery link is the mirror image of L11a289.

The Determinant and the Signature

(For In[1] see Setup)

| ||||

| ||||

Thus, for example, the knots 5_1 and 10_132 have the same determinant (and even the same Alexander and Jones polynomials), but different signatures:

5_1 |

10_132 |

In[4]:=

|

KnotDet /@ {Knot[5, 1], Knot[10, 132]}

|

Out[4]=

|

{5, 5}

|

In[5]:=

|

{

Equal @@ (Jones[#][q]& /@ {Knot[5, 1], Knot[10, 132]}),

Equal @@ (Alexander[#][t]& /@ {Knot[5, 1], Knot[10, 132]})

}

|

Out[5]=

|

{True, True}

|

In[6]:=

|

KnotSignature /@ {Knot[5, 1], Knot[10, 132]}

|

Out[6]=

|

{-4, 0}

|

In August 2005 somebody emailed Dror a question about knot colouring, which amounted to "find the first knot (other than the unknot) whose determinant is ". So on September 2nd Dror typed

In[7]:=

|

Select[AllKnots[], Abs[KnotDet[#]] == 1 &]

|

Out[7]=

|

{Knot[0, 1], Knot[10, 124], Knot[10, 153],

Knot[11, NonAlternating, 34], Knot[11, NonAlternating, 42],

Knot[11, NonAlternating, 49], Knot[11, NonAlternating, 116]}

|

Hence the first few knots that are not -colourable for any are 10_124, 10_153, K11n34, K11n42, K11n49 and K11n116.

K11n116 |

The Jones Polynomial

(For In[1] see Setup)

| ||||

In Naming and Enumeration we checked that the knots 6_1 and 9_46 have the same Alexander polynomial. Their Jones polynomials are different, though:

In[3]:=

|

Jones[Knot[6, 1]][q]

|

Out[3]=

|

-4 -3 -2 2 2

2 + q - q + q - - - q + q

q

|

In[4]:=

|

Jones[Knot[9, 46]][q]

|

Out[4]=

|

-6 -5 -4 2 -2 1

2 + q - q + q - -- + q - -

3 q

q

|

L8a6 |

On links with an even number of components the Jones polynomial is a function of , and hence it is often more convenient to view it as a function of , where :

In[5]:=

|

Jones[Link[8, Alternating, 6]][q]

|

Out[5]=

|

-(9/2) -(7/2) 3 3 4 3/2

-q + q - ---- + ---- - ------- + 3 Sqrt[q] - 2 q +

5/2 3/2 Sqrt[q]

q q

5/2 7/2

2 q - q

|

In[6]:=

|

PowerExpand[Jones[Link[8, Alternating, 6]][t^2]]

|

Out[6]=

|

-9 -7 3 3 4 3 5 7

-t + t - -- + -- - - + 3 t - 2 t + 2 t - t

5 3 t

t t

|

The Jones polynomial attains 2110 values on the 2226 knots and links known to KnotTheory`:

In[7]:=

|

all = Join[AllKnots[], AllLinks[]];

|

In[8]:=

|

Length /@ {Union[Jones[#][q]& /@ all], all}

|

Out[8]=

|

{2110, 2226}

|

How is the Jones polynomial computed?

(See also: The Kauffman Bracket using Haskell)

The Jones polynomial is so simple to compute using Mathematica that it's worthwhile pause and see how this is done, even for readers with limited prior programming experience. First, recall (say from [Kauffman]) the definition of the Jones polynomial using the Kauffman bracket :

| [KBDef] |

here is a commutative variable, , and is the writhe of , the difference where and count the positive Failed to parse (unknown function "\overcrossing"): {\displaystyle (\overcrossing)} and negative Failed to parse (unknown function "\undercrossing"): {\displaystyle (\undercrossing)} crossings of respectively.

Just for concreteness, let us start by fixing to be the trefoil knot shown above:

In[9]:=

|

L = PD[Knot[3, 1]]

|

Out[9]=

|

PD[X[1, 4, 2, 5], X[3, 6, 4, 1], X[5, 2, 6, 3]]

|

Our first task is to perform the replacement Failed to parse (unknown function "\slashoverback"): {\displaystyle \langle\slashoverback\rangle\to A\langle\hsmoothing\rangle + B\langle\smoothing\rangle} on all crossings of . By our conventions (see Planar Diagrams) the edges around a crossing are labeled , , and : Failed to parse (unknown function "\slashoverback"): {\displaystyle {}^c_d\slashoverback{}_a^b} . Labeling the smoothings Failed to parse (unknown function "\hsmoothing"): {\displaystyle (\hsmoothing, \ \smoothing)} in the same way, Failed to parse (unknown function "\hsmoothing"): {\displaystyle {}^c_d\hsmoothing{}_a^b} and Failed to parse (unknown function "\smoothing"): {\displaystyle {}^c_d\smoothing{}_a^b} , we are lead to the symbolic replacement rule . Let us apply this rule to , switch to a multiplicative notation and expand:

In[10]:=

|

t1 = L /. X[a_,b_,c_,d_] :> A P[a,d] P[b,c] + B P[a,b] P[c,d]

|

Out[10]=

|

PD[A P[1, 5] P[2, 4] + B P[1, 4] P[2, 5],

B P[1, 4] P[3, 6] + A P[1, 3] P[4, 6],

A P[2, 6] P[3, 5] + B P[2, 5] P[3, 6]]

|

In[11]:=

|

t2 = Expand[Times @@ t1]

|

Out[11]=

|

2

A B P[1, 4] P[1, 5] P[2, 4] P[2, 6] P[3, 5] P[3, 6] +

2 2

A B P[1, 4] P[2, 5] P[2, 6] P[3, 5] P[3, 6] +

2 2

A B P[1, 4] P[1, 5] P[2, 4] P[2, 5] P[3, 6] +

3 2 2 2

B P[1, 4] P[2, 5] P[3, 6] +

3

A P[1, 3] P[1, 5] P[2, 4] P[2, 6] P[3, 5] P[4, 6] +

2

A B P[1, 3] P[1, 4] P[2, 5] P[2, 6] P[3, 5] P[4, 6] +

2

A B P[1, 3] P[1, 5] P[2, 4] P[2, 5] P[3, 6] P[4, 6] +

2 2

A B P[1, 3] P[1, 4] P[2, 5] P[3, 6] P[4, 6]

|

In the above expression the product P[1,4] P[1,5] P[2,4] P[2,6] P[3,5] P[3,6] represents a path in which 1 is connected to 4, 1 is connected to 5, 2 is connected to 4, etc. (see the right half of the figure above). We simplify such paths by repeatedly applying the rules and :

In[12]:=

|

t3 = t2 //. {P[a_,b_]P[b_,c_] :> P[a,c], P[a_,b_]^2 :> P[a,a]}

|

Out[12]=

|

3 2

B P[1, 1] P[2, 2] P[3, 3] + A B P[2, 2] P[4, 4] +

3 2 2

A P[3, 3] P[4, 4] + A B P[3, 3] P[4, 4] + 3 A B P[5, 5] +

2

A B P[1, 1] P[5, 5]

|

To complete the computation of the Kauffman bracket, all that remains is to replace closed cycles (paths of the form by , to replace by , and to simplify:

In[13]:=

|

t4 = Expand[t3 /. P[a_,a_] -> -A^2-B^2 /. B -> 1/A]

|

Out[13]=

|

-9 1 3 7

-A + - + A + A

A

|

We could have, of course, combined the above four lines to a single very short program, that compues the Kauffman bracket from the beginning to the end:

In[14]:=

|

KB0[pd_] := Expand[

Expand[Times @@ pd /. X[a_,b_,c_,d_] :> A P[a,d] P[b,c] + 1/A P[a,b] P[c,d]]

//. {P[a_,b_]P[b_,c_] :> P[a,c], P[a_,b_]^2 :> P[a,a], P[a_,a_] -> -A^2-1/A^2}]

|

In[15]:=

|

t4 = KB0[PD[Knot[3, 1]]]

|

Out[15]=

|

-9 1 3 7

-A + - + A + A

A

|

We will skip the uninteresting code for the computation of the writhe here; it is a linear time computation, and if that's all we ever wanted to compute, we wouldn't have bothered to purchase a computer. For our the result is , and hence the Jones polynomial of is given by

In[16]:=

|

(-A^3)^(-3) * t4 / (-A^2-1/A^2) /. A -> q^(1/4) // Simplify // Expand

|

Out[16]=

|

-4 -3 1

-q + q + -

q

|

L11a548 |

At merely 3 lines of code, our program is surely nice and elegant. But it is very slow:

In[17]:=

|

time0 = Timing[KB0[PD[Link[11, Alternating, 548]]]]

|

Out[17]=

|

-23 5 10 -3 5 13 17 21 25

{1., A + --- + -- + A + 6 A + 6 A + 5 A - 5 A + 4 A - A }

15 7

A A

|

Here's the much faster alternative employed by KnotTheory`:

In[18]:=

|

KB1[pd_PD] := KB1[pd, {}, 1];

KB1[pd_PD, inside_, web_] := Module[

{pos = First[Ordering[Length[Complement[List @@ #, inside]]& /@ pd]]},

pd[[pos]] /. X[a_,b_,c_,d_] :> KB1[

Delete[pd, pos],

Union[inside, {a,b,c,d}],

Expand[web*(A P[a,d] P[b,c]+1/A P[a,b] P[c,d])] //. {

P[e_,f_]P[f_,g_] :> P[e,g], P[e_,_]^2 :> P[e,e], P[e_,e_] -> -A^2-1/A^2

}

]

];

KB1[PD[],_,web_] := Expand[web]

|

In[19]:=

|

time1 = Timing[KB1[PD[Link[11, Alternating, 548]]]]

|

Out[19]=

|

-23 5 10 -3 5 13 17 21

{0.015, A + --- + -- + A + 6 A + 6 A + 5 A - 5 A + 4 A -

15 7

A A

25

A }

|

(So on L11a548 KB1 is -23 5 10 -3 5 13 17 21 25

{1., A + --- + -- + A + 6 A + 6 A + 5 A - 5 A + 4 A - A }1,1

15 7

A A/ -23 5 10 -3 5 13 17 21 25

{0.015, A + --- + -- + A + 6 A + 6 A + 5 A - 5 A + 4 A - A }1,1

15 7

A A ~ -23 5 10 -3 5 13 17 21 25

{1., A + --- + -- + A + 6 A + 6 A + 5 A - 5 A + 4 A - A }1,1

15 7

A A

Round[--------------------------------------------------------------------------------]

-23 5 10 -3 5 13 17 21 25

{0.015, A + --- + -- + A + 6 A + 6 A + 5 A - 5 A + 4 A - A }1,1

15 7

A A times faster than KB0.)

The idea here is to maintain a "computation front", a planar domain which starts empty and gradualy increases until the whole link diagram is enclosed. Within the front, the rules defining the Kauffman bracket, Equation [KBDef], are applied and the result is expanded as much as possible. Outside of the front the link diagram remains untouched. At every step we choose a crossing outside the front with the most legs inside and "conquer" it -- apply the rules of [KBDef] and expand again. As our new outpost is maximally connected to our old territory, the length of the boundary is increased in a minimal way, and hence the size of the "web" within our front remains as small as possible and thus quick to manipulate.

In further detail, the routine KB1[pd, inside, web] computes the

Kauffman bracket assuming the labels of the edges inside the front are in

the variable inside, the already-computed inside of the front is in

the variable web and the part of the link diagram yet untouched is

pd. The single argument KB1[pd] simply calls

KB1[pd, inside, web] with an empty inside and with web set to 1. The three argument KB1[pd, inside, web] finds the position of the crossing maximmally connected to the front using the somewhat

cryptic assignment

pos = First[Ordering[Length[Complement[List @@ #, inside]]& /@ pd]]}

KB1[pd, inside, web] then recursively calls

itself with that crossing removed from pd}, with its legs

added to the inside, and with web updated in accordance

with [KBDef]. Finally, when pd is empty, the output is

simply the value of web.

[Kauffman] ^ L. H. Kauffman, On knots, Princeton Univ. Press, Princeton, 1987.

The Coloured Jones Polynomials

KnotTheory` can compute the coloured Jones polynomial of knots and links, using the formulas in [Garoufalidis Le]:

(For In[1] see Setup)

In[2]:=

?ColouredJones

ColouredJones[K, n][q] returns the coloured Jones polynomial of a knot in colour n (i.e., in the (n+1)-dimensional representation) in the indeterminate q. Some of these polynomials have been precomputed in KnotTheory`. To force computation, use ColouredJones[K,n, Program -> "prog"][q], with "prog" replaced by one of the two available programs, "REngine" or "Braid" (including the quotes). "REngine" (default) computes the invariant for closed knots (as well as links where all components are coloured by the same integer) directly from the MorseLink presentation of the knot, while "Braid" computes the invariant via a presentation of the knot as a braid closure. "REngine" will usually be faster, but it might be better to use "Braid" when (roughly): 1) a "good" braid representative is available for the knot, and 2) the length of this braid is less than the maximum width of the MorseLink presentation of the knot.

In[3]:=

ColouredJones::about

The "REngine" algorithm was written by Siddarth Sankaran in the summer of 2005, while the "Braid" algorithm was written jointly by Dror Bar-Natan and Stavros Garoufalidis. Both are based on formulas by Thang Le and Stavros Garoufalidis; see [Garoufalidis, S. and Le, T. "The coloured Jones function is q-holonomic." Geom. Top., v9, 2005 (1253-1293)].

Thus, for example, here's the coloured Jones polynomial of the knot

4_1 in the 4-dimensional representation of :

In[4]:=

ColouredJones[Knot[4, 1], 3][q]

Out[4]=

-12 -11 -10 2 2 3 3 2 4 6

3 + q - q - q + -- - -- + -- - -- - 3 q + 3 q - 2 q +

8 6 4 2

q q q q

8 10 11 12

2 q - q - q + q

And here's the coloured Jones polynomial of the same knot in the two

dimensional representation of ; this better be equal to the ordinary

Jones polynomial of 4_1!

In[5]:=

ColouredJones[Knot[4, 1], 1][q]

Out[5]=

-2 1 2

1 + q - - - q + q

q

In[6]:=

Jones[Knot[4, 1]][q]

Out[6]=

-2 1 2

1 + q - - - q + q

q

4_1

3_1

In[7]:=

?CJ`Summand

CJ`Summand[br, n] returned a pair {s, vars} where s is the summand in the the big sum that makes up ColouredJones[br, n][q] and where vars is the list of variables that need to be summed over (from 0 to n) to get ColouredJones[br, n][q]. CJ`Summand[K, n] is the same for knots for which a braid representative is known to this program.

The coloured Jones polynomial of 3_1 is computed via a single summation. Indeed,

In[8]:=

s = CJ`Summand[Mirror[Knot[3, 1]], n]

Out[8]=

(3 n)/2 + n CJ`k[1] + (-n + 2 CJ`k[1])/2 1

{CJ`q qBinomial[0, 0, ----]

CJ`q

1 1

qBinomial[CJ`k[1], 0, ----] qBinomial[CJ`k[1], CJ`k[1], ----]

CJ`q CJ`q

n 1 n 1

qPochhammer[CJ`q , ----, 0] qPochhammer[CJ`q , ----, CJ`k[1]]

CJ`q CJ`q

n - CJ`k[1] 1

qPochhammer[CJ`q , ----, 0], {CJ`k[1]}}

CJ`q

The symbols in the above formula require a definition:

In[9]:=

?qPochhammer

qPochhammer[a, q, k] represents the q-shifted factorial of a in base q with index k. See Eric Weisstein's

http://mathworld.wolfram.com/q-PochhammerSymbol.html and Axel Riese's

www.risc.uni-linz.ac.at/research/combinat/risc/software/qMultiSum/

In[10]:=

?qBinomial

qBinomial[n, k, q] represents the q-binomial coefficient of n and k in base q. For k<0 it is 0; otherwise it is

qPochhammer[q^(n-k+1), q, k] / qPochhammer[q, q, k].

More precisely, qPochhammer[a, q, k] is

and qBinomial[n, k, q] is

The function qExpand replaces every occurence of a qPochhammer[a, q, k]

symbol or a qBinomial[n, k, q] symbol by its definition:

In[11]:=

?qExpand

qExpand[expr_] replaces all occurences of qPochhammer and qBinomial in expr by their definitions as products. See the documentation for qPochhammer and for qBinomial for details.

Hence,

In[12]:=

qPochhammer[a, q, 6] // qExpand

Out[12]=

2 3 4 5

(-1 + a) (-1 + a q) (-1 + a q ) (-1 + a q ) (-1 + a q ) (-1 + a q )

In[13]:=

First[s] /. {n -> 3, CJ`k[1] -> 2} // qExpand

Out[13]=

11 2 3

CJ`q (-1 + CJ`q ) (-1 + CJ`q )

Finally,

In[14]:=

?ColoredJones

Type ColoredJones and see for yourself.

[Garoufalidis Le] ^ S. Garoufalidis and T. Q. T. Le, The Colored Jones Function is -Holonomic, Georgia Institute of Technology preprint, September 2003, arXiv:math.GT/0309214.

The A2 Invariant

We compute the (or quantum ) invariant using the normalization and formulas of [Khovanov], which in itself follows [Kuperberg]:

(For In[1] see Setup)

In[2]:=

?A2Invariant

A2Invariant[L][q] computes the A2 (sl(3)) invariant of a knot or link L as a function of the variable q.

As an example, let us check that the knots 10_22 and 10_35 have the same Jones polynomial but different invariants:

In[3]:=

Jones[Knot[10, 22]][q] == Jones[Knot[10, 35]][q]

Out[3]=

True

In[4]:=

A2Invariant[Knot[10, 22]][q]

Out[4]=

-12 -8 -6 -4 2 4 6 8 10 12 14

-1 + q + q + q - q + -- - q - 2 q + q - q + q + q +

2

q

18

q

In[5]:=

A2Invariant[Knot[10, 35]][q]

Out[5]=

-14 -12 -10 -8 2 2 2 6 8 10 14 16

q + q - q + q - -- + -- + q - q + q - 2 q + q - q +

4 2

q q

18 20

q + q

The invariant attains 2163 values on the 2226 knots and links known to KnotTheory:

In[6]:=

all = Join[AllKnots[], AllLinks[]];

In[7]:=

Length /@ {Union[A2Invariant[#][q]& /@ all], all}

Out[7]=

{2163, 2226}

[Khovanov] ^ M. Khovanov, link homology I, arXiv:math.QA/0304375.

[Kuperberg] ^ G. Kuperberg, Spiders for rank 2 Lie algebras, Comm. Math. Phys. 180 (1996) 109-151, arXiv:q-alg/9712003.

The HOMFLY-PT Polynomial

The HOMFLY-PT polynomial (see [HOMFLY] and [PT]) of a knot or link is defined by the skein relation

Failed to parse (unknown function "\overcrossing"): {\displaystyle aH\left(\overcrossing\right)-a^{-1}H\left(\undercrossing\right)=zH\left(\smoothing\right) }

and by the initial condition =1.

KnotTheory` knows about the HOMFLY-PT polynomial:

(For In[1] see Setup)

In[2]:=

?HOMFLYPT

HOMFLYPT[K][a, z] computes the HOMFLY-PT (Hoste, Ocneanu, Millett, Freyd, Lickorish, Yetter, Przytycki and Traczyk) polynomial of a knot/link K, in the variables a and z.

In[3]:=

HOMFLYPT::about

The HOMFLYPT program was written by Scott Morrison.

Thus, for example, here's the HOMFLY-PT polynomial of the knot 8_1:

In[4]:=

K = Knot[8, 1];

In[5]:=

HOMFLYPT[Knot[8, 1]][a, z]

Out[5]=

-2 4 6 2 2 2 4 2

a - a + a - z - a z - a z

It is well known that HOMFLY-PT polynomial specializes to the Jones polynomial at and and to the Conway polynomial at . Indeed,

In[6]:=

Expand[HOMFLYPT[K][1/q, Sqrt[q]-1/Sqrt[q]]]

Out[6]=

-6 -5 -4 2 2 2 2

2 + q - q + q - -- + -- - - - q + q

3 2 q

q q

In[7]:=

Jones[K][q]

Out[7]=

-6 -5 -4 2 2 2 2

2 + q - q + q - -- + -- - - - q + q

3 2 q

q q

In[8]:=

{HOMFLYPT[K][1, z], Conway[K][z]}

Out[8]=

2 2

{1 - 3 z , 1 - 3 z }

8_1

L5a1

In our parametrization of the link invariant, it satisfies

, where is some knot or link and where is the number of components of . Let us verify this fact for the Whitehead link, L5a1:

In[9]:=

L = Link[5, Alternating, 1];

In[10]:=

Simplify[{

(-1)^(Length[Skeleton[L]]-1)(q^2+1+1/q^2)HOMFLYPT[L][1/q^3, q-1/q],

A2Invariant[L][q]

}]

Out[10]=

-12 -8 -6 2 -2 2 4 6

{2 - q + q + q + -- + q + q + q + q ,

4

q

-12 -8 -6 2 -2 2 4 6

2 - q + q + q + -- + q + q + q + q }

4

q

Other Software to Compute the HOMFLY-PT Polynomial

A C-based program running under windows by M. Ochiai can compute the HOMFLY-PT polynomial of certain knots and links with up to hundreds of crossings using "base tangle decompositions". His program, bTd, is available at [1].

References

[HOMFLY] ^ J. Hoste, A. Ocneanu, K. Millett, P. Freyd, W. B. R. Lickorish and D. Yetter, A new polynomial invariant of knots and links, Bull. Amer. Math. Soc. 12 (1985) 239-246.

[PT] ^ J. Przytycki and P. Traczyk, Conway Algebras and Skein Equivalence of Links, Proc. Amer. Math. Soc. 100 (1987) 744-748.

The Kauffman Polynomial

The Kauffman polynomial (see [Kauffman]) of a knot or link is where is the writhe of (see How is the Jones Polynomial Computed?) and where is the regular isotopy invariant defined by the skein relations

(here is a strand and is the same strand with a kink added) and

Failed to parse (unknown function "\backoverslash"): {\displaystyle L(\backoverslash)+L(\slashoverback) = z\left(L(\smoothing)+L(\hsmoothing)\right)}

and by the initial condition where is the unknot  .

.

KnotTheory` knows about the Kauffman polynomial:

(For In[1] see Setup)

In[2]:=

?Kauffman

Kauffman[K][a, z] computes the Kauffman polynomial of a knot or link K, in the variables a and z.

In[3]:=

Kauffman::about

The Kauffman polynomial program was written by Scott Morrison.

Thus, for example, here's the Kauffman polynomial of the knot 5_2:

In[4]:=

Kauffman[Knot[5, 2]][a, z]

Out[4]=

2 4 6 5 7 2 2 4 2 6 2 3 3

-a + a + a - 2 a z - 2 a z + a z - a z - 2 a z + a z +

5 3 7 3 4 4 6 4

2 a z + a z + a z + a z

5_2

T(8,3)

It is well known that the Jones polynomial is related to the Kauffman polynomial via

, where is some knot or link and where is the number of components of . Let us verify this fact for the torus knot T(8,3):

In[5]:=

K = TorusKnot[8, 3];

In[6]:=

Simplify[{

(-1)^(Length[Skeleton[K]]-1)Kauffman[K][-q^(-3/4), q^(1/4)+q^(-1/4)],

Jones[K][q]

}]

Out[6]=

7 9 16 7 9 16

{q + q - q , q + q - q }

[Kauffman] ^ L. H. Kauffman, An invariant of regular isotopy, Trans. Amer. Math. Soc. 312 (1990) 417-471.

Finite Type (Vassiliev) Invariants

(For In[1] see Setup)

In[2]:=

?Vassiliev

Vassiliev[2][K] computes the (standardly normalized) type 2 Vassiliev invariant of the knot K, i.e., the coefficient of z^2 in Conway[K][z]. Vassiliev[3][K] computes the (standardly normalized) type 3 Vassiliev invariant of the knot K, i.e., 3J''(1)-(1/36)J'''(1) where J is the Jones polynomial of K.

Thus, for example, let us reproduce Willerton's "fish" (arXiv:math.GT/0104061), the result of plotting the values of against the values of , where is the (standardly normalized) type 2 invariant of , is the (standardly normalized) type 3 invariant of , and where runs over a set of knots with equal crossing numbers (10, in the example below):

As another example, let us consider the expansion of the Jones polynomial for a knot as a power series in when we substitute the standard variable with and use the power series expansion of :

Then, for the above coefficients we have that and for all is a Vassiliev invariant of type [BirmanLin].

We can see this result by using the invariant formula:

Failed to parse (unknown function "\doublepoint"): {\displaystyle V\left(\doublepoint\right)= V\left(\overcrossing\right)-V\left(\undercrossing\right)}

to check the Birman-Lin condition, which tells us that an invariant is of type if it vanishes on knots with more than double points, or self intersections (see [Bar-Natan]). Computing on knots with more than one double point by resolving one self intersection at a time, it is enough to check that vanishes on knots with double points:

Failed to parse (unknown function "\doublepoint"): {\displaystyle V\underbrace{ \left(\doublepoint\cdots\doublepoint\right) }_{m+1}=0}

The following two programs let us determine for any integer and knot :

In[4]:=

SetCrossing[K_, l_Integer, s_] := Module[

{pd, n},

pd = PD[K];

If[PositiveQ[pd[[l]]],

If[s == "-", pd[[l]] = RotateRight@pd[[l]]],

If[s == "+", pd[[l]] = RotateLeft@pd[[l]]]];

pd];

In[5]:=

V[K_, n_] := Series[Jones[K][Exp[x]], {x, 0, n}];

V[K_, n_, {i1_, is___}] :=

V[SetCrossing[K, i1, "+"], n, {is}] -

V[SetCrossing[K, i1, "-"], n, {is}];

V[K_, n_, {}] := V[K, n];

The first program, SetCrossing, sets the crossing of a knot to be positive or negative depending on whether we choose to be "" or "". The second program uses the invariant formula to give the series expansion of the Jones polynomial of a knot discussed above, up to order , where a selected list of the crossings of are taken as double points. is then the coefficient of the term containing .

For example, we can check that disappears on the knot 9_47 with its first five crossings taken as double points:

In[6]:=

V[Knot[9, 47], 4, {1, 2, 3, 4, 5}]

Out[6]=

V[Knot[9, 47], 4, {1, 2, 3, 4, 5}]

The knot 9_47 with its first five crossings taken as double points.

The knot 9_47 with its first five crossings taken as double points.[Bar-Natan] ^ D. Bar-Natan, On the Vassiliev Knot Invariants, Topology 34 (1995) 423-472.

[BirmanLin] ^ J.S. Birman and X.-S. Lin, Knot Polynomials and Vassiliev's Invariants, Invent. Math. 111 (1993) 225-270.

Khovanov Homology

(See also: Tweaking JavaKh)

The Khovanov Homology of a knot or a link , also known as Khovanov's categorification of the Jones polynomial of , was defined by Khovanov in [Khovanov1] (also check [Bar-Natan1]), where the notation is closer to the notation used here). It is a graded homology theory; each homology group is in itself a direct sum of homogeneous components. Over a field one can form the two-variable "Poincaré polynomial" (which deserves the name "the Khovanov polynomial of "),

. (For In[1] see Setup)

In[2]:=

?Kh

Kh[L][q, t] returns the Poincare polynomial of the Khovanov Homology of a knot/link L (over a field of characteristic 0) in terms of the variables q and t. Kh[L, Program -> prog] uses the

program prog to perform the computation. The currently available programs are "FastKh", written in Mathematica by Dror Bar-Natan in the winter of 2005, "JavaKh-v1", written in java (java 1.5

required!) by Jeremy Green in the summer of 2005 and "JavaKh-v2" (default), an update of "JavaKh-v1" (now requiring java 1.6) written by Scott Morrison in 2008.

("JavaKh" is also available, currently an alias for "JavaKh-v2".)

The java programs are several thousand times faster than the Mathematica program, though java may not be available on some systems. "JavaKh2" also takes the option "Modulus -> p" which changes the characteristic of the ground field to p. If p==0 JavaKh works over the rational numbers; if p==Null JavaKh works over Z (see ?ZMod for the output format).

Thus for example, here's the Khovanov polynomial of the knot 5_1:

In[3]:=

kh = Kh[Knot[5, 1]][q, t]

Out[3]=

-5 -3 1 1 1 1

q + q + ------ + ------ + ------ + -----

15 5 11 4 11 3 7 2

q t q t q t q t

The Euler characteristic of the Khovanov Homology is (up to normalization) the Jones polynomial of . Precisely,

. Let us verify this in the case of 5_1:

In[4]:=

{kh /. t -> -1, Expand[(q+1/q)Jones[Knot[5, 1]][q^2]]}

Out[4]=

-15 -7 -5 -3 -15 -7 -5 -3

{-q + q + q + q , -q + q + q + q }

5_1

10_132

Khovanov's homology is a strictly stronger invariant than the Jones polynomial. Indeed, though :

In[5]:=

{

Jones[Knot[5, 1]] === Jones[Knot[10, 132]],

Kh[Knot[5, 1]] === Kh[Knot[10, 132]]

}

Out[5]=

{True, False}

The algorithm presently used by KnotTheory` is an efficient algorithm modeled on the Kauffman bracket algorithm of The Jones Polynomial, as explained in [Bar-Natan3] (which follows [Bar-Natan2]). Currently, two implementations of this algorithm are available:

- FastKh: My original implementation, written in Mathematica in the winter of 2005. This implementation can be explicitly invoked using the syntax

Kh[L, Program -> "FastKh"][q, t] or by changing the default behaviour of Kh by evaluating SetOptions[Kh, Program -> "FastKh"].

- JavaKh: In the summer of 2005 Jeremy Green re-implemented the algorithm in java (java 1.5 required, can be had from http://java.sun.com/) with much further care to the details, leading to an improvement factor of several thousands for large knots/links. This implementation is the default. It can also be explicitly invoked from within Mathematica using the syntax

Kh[L, Program -> "JavaKh"][q, t].

In[6]:=

Options[Kh]

Out[6]=

{ExpansionOrder -> Automatic, Program -> JavaKh-v2, Modulus -> 0,

KnotTheory`FastKh`Universal -> False, JavaOptions -> }

JavaKh takes an additional option, Modulus, which sets the characteristic of the ground field for the homology computations to or to a prime . Thus for example, the following four In lines imply that the Khovanov homology of the torus knot T(6,5) has both 3 torsion and 5 torsion, but no 7 torsion:

In[7]:=

T65 = TorusKnot[6, 5]; kh = Kh[T65][q, t];

In[8]:=

Kh[T65, Modulus -> 3][q, t] - kh

Out[8]=

43 13 43 14

q t + q t

In[9]:=

Kh[T65, Modulus -> 5][q, t] - kh

Out[9]=

35 10 35 11 39 11 39 12

q t + q t + q t + q t

In[10]:=

Kh[T65, Modulus -> 7][q, t] - kh

Out[10]=

0

T(6,5)

The following further example is a bit tougher. It takes my computer nearly an hour and some 256Mb of memory to find that the Khovanov homology of the 48-crossing torus knot T(8,7) has 3, 5 and 7 torsion but no 11 torsion:

In[11]:=

?JavaOptions

JavaOptions is an option to Kh. Kh[L, Program -> "JavaKh2", JavaOptions -> jopts] calls java with options jopts. Thus for example, JavaOptions -> "-Xmx256m" sets the maximum java heap size to 256MB - useful for large computations.

In[12]:=

SetOptions[Kh, JavaOptions -> "-Xmx256m"];

In[13]:=

T87 = TorusKnot[8, 7]; kh = Kh[T87][q, t];

In[14]:=

Factor[Kh[T87, Modulus -> 3][q, t] - kh]

Out[14]=

79 25

q t (1 + t)

In[15]:=

Factor[Kh[T87, Modulus -> 5][q, t] - kh]

Out[15]=

61 11 12 10 14 12 18 13

q t (1 + t) (1 + q t + q t + q t )

In[16]:=

Factor[Kh[T87, Modulus -> 7][q, t] - kh]

Out[16]=

61 14 8 6 12 7 10 8 14 9

q t (1 + t) (1 + q t + q t + q t + q t )

In[17]:=

Factor[Kh[T87, Modulus -> 11][q, t] - kh]

Out[17]=

0

JavaKh also works over the integers:

In[18]:=

?ZMod

ZMod[m] denotes the cyclic group Z/mZ. Thus if m=0 it is the infinite cyclic group Z and if m>0 it is the finite cyclic group with m elements. ZMod[m1, m2, ...] denotes the direct sum of ZMod[m1], ZMod[m2], ... .

For example, the 22nd homology group over of the torus knot T(8,7) at degree 73 is the 280 element torsion group :

In[19]:=

Coefficient[Kh[T87, Modulus -> Null][q, t], t^22 * q^73]

Out[19]=

ZMod[2, 4, 5, 7]

T(8,7) is currently not on the Knot Atlas. Let us see what it looks like:

In[20]:=

Show[TubePlot[TorusKnot[8, 7]]]

Out[20]=

-Graphics3D-

Finally, JavaKh may also be run outside of Mathematica, as the following example demonstrates:

drorbn@coxeter:.../KnotTheory: cd JavaKh

drorbn@coxeter:.../KnotTheory/JavaKh: java JavaKh

PD[X[3, 1, 4, 6], X[1, 5, 2, 4], X[5, 3, 6, 2]]

"+ q^1t^0 + q^3t^0 + q^5t^2 + q^9t^3 "

(Type java JavaKh -help for some further help).

(Warning, as of August 2008, you need to include the .jar files in JavaKh/jars on the classpath. If this causes confusion, ask Scott for a script that manages this automatically, or look at p. 29 of [2] for an example.)

Universal Khovanov homology, and reduced homology